Learning More About the Black Experience

Celebrating Black History Month The Black Family: Representation, Identity, and Diversity

How will we celebrate Black History Month this year? How will we take it from a place of token acknowledgment to one of lasting impact?

With all the efforts of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020 to promote a world where systemic racism comes to an end and those oppressed can finally live a life free of the fear of injustice waiting for them at every turn, Black History Month takes on another layer of meaning.

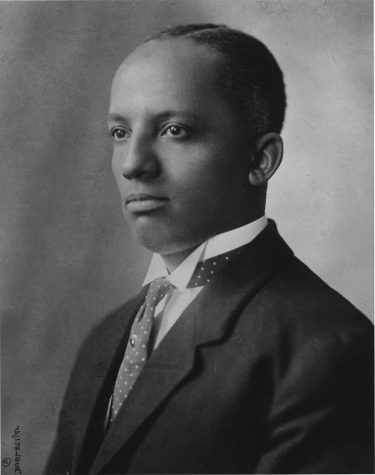

As we promote the legacy of the Harvard-trained historian Carter G. Woodson and minister Jesse E. Moorland, founders of what is now known as the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH), and creators of what has evolved from Negro History Week into Black History Month, what will we do differently?

The 2021 theme for Black History Month is The Black Family: Representation, Identity, and Diversity.

The Black family has been the topic of discussion in several forms—history, literature, art, film, social policy, etc., and it is here where the identity and representation of the Black community has been stereotyped and vilified.

Ellian Phillinganes ‘23 said, “The Black family is one that has been stereotyped negatively in media so I’m glad they’re being highlighted now.”

There is no single location the black family knows because of the separation and spread of family members across states, countries and continents—the product of the African Diaspora.

According to Colin A. Palmer, a distinguished professor of history at the Graduate School and University Center of the City University of New York, There are five major African diasporic streams, but it is the last two, that he believes make up the modern African Diaspora.

In his article “Defining and Studying the Modern African Diaspora.” published in Perspectives on History, the news magazine of the National Historical Association, he stated: “The fourth major African diasporic stream, and the one that is most widely studied today, is associated with the Atlantic trade in African slaves. This trade, which began in earnest in the 15th century, may have delivered as many as 200,000 Africans to various European societies and 11 to 12 million to the Americas over time.

The fifth major stream began during the 19th century particularly after slavery’s demise in the Americas and continues to our own times. It is characterized by the movement of Africans and peoples of African descent among, and their resettlement in, various societies.”

What is interesting about this definition is the way it unifies a group of people.

Palmer wrote: “The modern African diaspora, at its core, consists of the millions of peoples of African descent living in various societies who are united by a past based significantly but not exclusively upon “racial” oppression and the struggles against it; and who, despite the cultural variations and political and other divisions among them, share an emotional bond with one another and with their ancestral continent; and who also, regardless of their location, face broadly similar problems in constructing and realizing themselves.”

It is not surprising that the portrayal of the Black family and its meaning is so complex even as it serves as a foundational concept of African American life and history.

In his Smithsonian magazine article “The Changing Definition of African-American,” Ira Berlin, author and professor at the University of Maryland, wrote about how the influx of people from Africa and the Caribbean to America in since 1965 has created more layers to the definition of what it means to be Black in America.

“To many of these men and women [more recent immigrants], Juneteenth celebrations—the commemoration of the end of slavery in the United States—are at best an afterthought,” wrote Berlin. “The new arrivals frequently echo the words of the men and women I met outside the radio broadcast booth. Some have struggled over the very appellation ‘African-American,’ either shunning it—declaring themselves, for instance, Jamaican-Amer-icans or Nigerian-Americans—or denying native black Americans’ claim to it on the ground that most of them had never been to Africa. At the same time, some old-time black residents refuse to recognize the new arrivals as true African-Americans.”

The cultural landscape continues to change, as does our understanding of the Black family.

How DO we represent the Black family, especially from a historical perspective? Is it enslaved or free, or is it a single-headed or dual-headed household? Extended or nuclear? Black or interracial?

Berlin’s understanding might be the one we need to take.

“After devoting more than 30 years of my career as a historian to the study of the American past, I’ve concluded that African-American history might best be viewed as a series of great migrations, during which immigrants—at first forced and then free—transformed an alien place into a home, becoming deeply rooted in a land that once was foreign, even despised. After each migration, the newcomers created new understandings of the African-American experience and new definitions of blackness,” wrote Berlin.

So many questions arise when wanting to accurately describe the Black family, but so much variations appear.

But it is in those variations where the Black Family finds its rich, story-telling squares that weave together the past, present and future.

Despite the pandemic, there are several COVID-friendly ways to celebrate Black History Month.

Throughout February, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture is hosting virtual events, allowing the public to join in the conversation and to recognize and appreciate the history of the Black community.

Deirdre Cross, NMAAHC’s director of public programs said, “Understanding the African American lens on American history demonstrates the resilience of the African American community. People have struggled for their place in this democracy. It shows how there are historic issues of contemporary importance. Our generation is able to pick up its part in making this really a more perfect union for American communities at large.”

As we celebrate Black History Month, it is fitting that we recognize and celebrate the Black family in all of its representations, identifications, and diversity.

There is no “cookie-cutter” definition of the Black family, and the moment we recognize that, the closer we will come to achieving Dr. King’s dream.

“I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed — we hold these truths to be self-evident: that all [people] are created equal.”