“You may be whatever you resolve to be.”

-Words taken from “Stonewall” Jackson’s challenge to cadets at the Virginia Military Institute.

Out of all the soldiers that fought for the United States in World War 2, only one African American infantry division was allowed to see combat in Europe: The Buffalo Soldiers, formally known as the 92nd Infantry Division.

Founded on Oct. 15, 1942, in Fort McClellan, Ala., the 92nd Infantry Division was composed of white officers and African American enlisted soldiers. They were only one of three segregated African American divisions in the U.S., which were dubbed the “Colored Troops”.

The army’s requirements for well-trained soldiers (those that would be sent to war) directly combatted the realities of race-based education in the 1930s.

The African American soldier’s inadequate education became clear when 13 percent of the division were found to be illiterate, and 62 percent were found to belong in the lowest classification categories, which the army often deemed as “untrainable” and “unreliable.”

Because of this, the division required 8 months more of training than similar all-white divisions.

The Buffalo Soldiers were deployed to Italy in the fall of 1944, after only a year of training together, and joined the continued assault to the Alps. This continued assault aimed to root out the German units defending the Italian Alps. This was some of the most difficult fighting in the entire Italian campaign.

The division faced many setbacks and complete failures because of ineffective officer leadership due to the division’s segregation. Maintaining unit cohesion was far more difficult.

That is not to say that the division was not successful. From August of 1944 to the end of the war in May of 1945, the 92nd Infantry Division advanced 3,000 square miles and captured over 20,000 German prisoners.

Sadly, as with any war, this was not without suffering casualties in the thousands.

After the war, the 92nd Infantry Division returned home and were formally inactivated on Nov. 28, 1945. The U.S. never fielded another segregated division again, even though full integration in the army would not come for many years. The 92nd Infantry Division proved the strength and excellence of African American soldiers and proved the weakness within the military system.

In 1948, President Truman ordered the military to integrate, though this did not fully happen until the Korean War in the early 1950s.

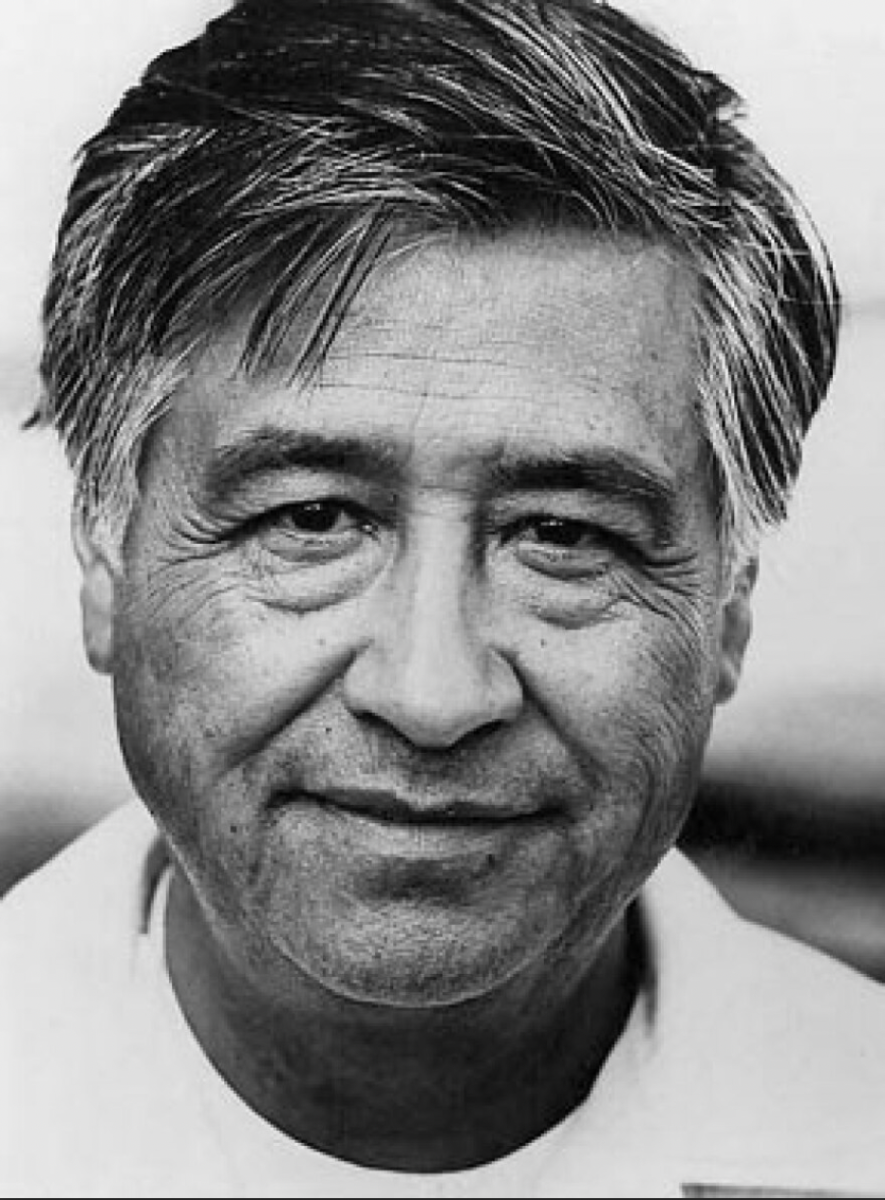

Within the 92nd Infantry, two soldiers received the Medal of Honor: First Lieutenant Vernon Baker and First Lieutenant John R. Fox.

First Lieutenant Vernon Baker was born Dec. 17, 1919, later joining the military in 1941 at the age of 22. Four years later, on April 5, 1945, he led an advance on the German stronghold Castle Aghinolfi.

Baker and 25 men went ahead, arriving at the stronghold at 5 a.m. However, while setting up a machine gun position, Lieutenant Baker spotted what seemed to be two circular objects peeking out of the wall.

Upon further inspection, he discovered several German soldiers. Eliminating multiple enemy soldiers before rushing to help his allies, Baker effectively eliminated one German observation post, a dugout, 3 machine gun positions, and a total of nine enemy soldiers.

The next day, April 6, Baker voluntarily led a battalion through German minefields and fire to achieve their goal: an occupied mountain.

After the war ended, Baker served 23 more years in the military before retiring and then dedicated over 20 more years to the Red Cross.

On Jan. 13, 1997, First Lieutenant Vernon Baker received a Medal of Honor from President Bill Clinton for his actions and bravery in World War 2. He was one of seven recipients, but Baker was the only one alive to receive his medal.

One of the other six Medal of Honor recipients was also a member of the 92nd Infantry Division: First Lieutenant John R. Fox.

Born on May 18, 1915, Fox joined the army in 1941, the same year as Baker. However, only three years later, Fox would risk his life to delay German advances in the Serichio River Valley of Italy.

Fox Hand his team arrived on Dec. 23, 1944, to set up observation posts to monitor the town of Sommocolonia. Two days later, on Christmas Day, German soldiers dressed in civilian clothes attempted to infiltrate the town. Noticing this, Fox ordered the rest of his team to retreat while he would stay behind.

Fox began to order artillery strikes, each getting closer and closer to his position, and on December 26, 1944, Fox requested an artillery strike on his exact coordinates.

Despite his battalion commander’s protests, the strike was completed, delaying German forces for a week and allowing American troops to effectively secure Sommocolonia.

When the town was secured, they discovered Fox’s body.

Five decades later, First Lieutenant John R Fox was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions that day. His widow, Mrs. Arlene E. Fox, was there to receive it in his place.

At the end of World War 2, 53 members of the 92nd Infantry Division were unaccounted for, but it would not be until 2014 that a formal effort was made to find and honor these soldiers.

The Defense Prisoner of War/Missing in Action Accounting Association (DPAA) called for the 92nd Infantry Project in 2014. Through this project, three members have been accounted for. Yet, the DPAA has not stopped looking, even with the struggles posed by finding matches of DNA.

The 92nd Infantry Division is not simply a military division, but an important part of United States history.

These soldiers not only had to fight the Axis powers, but also the prejudice and hatred from within their own government and allies.

Today, history recounts how their efforts assisted securing locations in Italy, but also helped end segregation in the military as well.

The Buffalo Soldiers, an integral part of the U.S. military, are remembered for their bravery, resilience, and perseverance.